Story highlights

NEW: Six planes continue search in remote Indian Ocean

So far no sign of objects seen by satellite

What was up with pilot's call, and were batteries aboard the plane dangerous?

Australian officials have said the objects could be from Flight 370

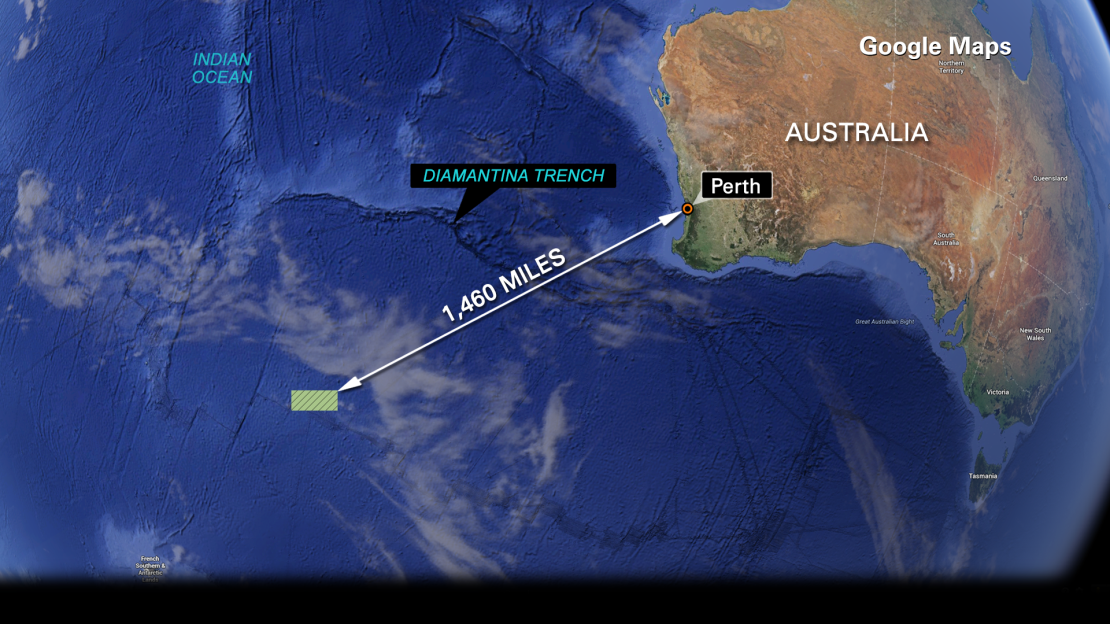

Two weeks after the disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370, finding it remains a global search-and-rescue effort. The bulk of the attention is on the southern Indian Ocean, where a commercial satellite photographed objects that Australian authorities say could be related to the search.

Authorities have called the find the best lead yet on where the missing plane might be, and it has prompted a massive search in the area more than 1,500 miles (2,400 kilometers) southwest of Australia. So far, they have turned up nothing.

What’s the very latest?

Australian officials say six planes were continuing the search Saturday after nothing was found in the area Friday.

Britain’s The Telegraph published what it said was part of a transcript of the final communications between the Malaysia Airlines flight cockpit and air traffic controllers. It shows only routine technical chatter. CNN has not independently verified that the transcript is genuine.

The CEO of Malaysia Airlines confirmed that the plane was carrying lithium-ion batteries. And authorities said they’re aware of a news report that the plane’s pilot placed a cell phone call shortly before the flight departed.

What’s the significance of the phone call?

There may not be any, but in a mystery as big as this one, investigators will check out any lead to see if it’s important.

And what about the batteries?

Lithium-ion batteries are the type commonly used in laptops and cell phones, and have been known to explode, although it is a rare occurrence.

A fire attributed to lithium-ion batteries caused the fatal 2010 crash of a UPS cargo plane in Dubai. Lithium-ion batteries used to power components in Boeing 787 aircraft were also implicated in a series of fires affecting that plane.

So, in theory, a cargo of the batteries could have caused a fire that led Flight 370 to crash.

But Malaysia Airlines CEO Ahmad Jauhari Yahya told reporters the batteries were routine cargo.

“They are not declared dangerous goods,” he said, adding that they were “some small batteries, not big batteries.”

It’s been two days since we saw the satellite photos of floating objects. Why haven’t searchers found anything?

The area being searched is enormous and remote. Aircraft can stay over the scene just two hours before having to return to base. And given that the objects spotted on satellite could have drifted hundreds of miles since they were photographed Sunday, or maybe have even sunk by now, finding them isn’t a simple proposition.

Japan is sending surveillance planes, more merchant ships are on the way, and Australia, Britain, China and Malaysia are all sending ships to the area – a remote region far from commercial shipping and air lanes.

Is it possible that the plane would have gone that far?

Investigators think so. They concluded the plane flew for hours after disappearing from radar, and calculated a pair of arcs running north and south from the Malay Peninsula for likely locations. Based on those trajectories, the amount of fuel on board and other factors, experts believe the plane could have made it to the southern Indian Ocean.

When will we know whether the objects are from the missing flight?

Maybe never. Searchers might miss them, or they might have sunk by now.

But even if they do find the objects, the process of determining whether they’re from the missing flight could still be lengthy.

“We have to locate it, confirm that it belongs to the aircraft, recover it and then bring it a long way back to Australia, so that could take some time,” said John Young, general manager of emergency response for the Australian Maritime Safety Authority,

Could pieces of the plane still be floating?

Probably not any big pieces, according to Steve Wallace, the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration’s former director of accident investigation. But pieces of lightweight debris, such as life jackets and seat cushions, can float for days after an aircraft strikes the water, he said.

If it’s not the plane, what else could it be?

Almost anything big and buoyant. The objects were spotted in a part of the Indian Ocean known for swirling currents called gyres that can trap all sorts of floating debris. Among the leading contenders for what the objects might be, assuming they’re not part of Flight 370: shipping containers that fell off a passing cargo vessel. There are reasons to doubt that theory, however. The area isn’t near commercial shipping lanes, and the larger object, at an estimated 79 feet (24 meters), would seem to be nearly twice as long as a standard shipping container.

If it is the plane, would its location tell us anything about what happened on that flight?

If it really is the wreckage of the Boeing 777-200, its far southern location would provide investigators with precious clues into what terrible events unfolded to result in the disappearance and loss of the airliner, according to Robert Goyer, editor-in-chief of Flying magazine and a commercial jet-rated pilot. “The location would suggest a few very important parameters. The spot where searchers have found hoped-for clues is, based on the location information provided by the Australian government, nearly 4,000 miles from where the airliner made its unexpected and as yet unexplained turn to the west,” Goyer wrote. The first obvious clue is that the airplane flew for many hours.

What do the satellite images show?

Two indistinct objects, one about 79 feet (24 meters) in length and the other about 16 feet (5 meters) long. Though they don’t look like much to the untrained observer, Australian intelligence imagery experts who looked at the pictures saw enough to pass them along to the maritime safety agency, Young said. “Those who are expert indicate they are credible sightings. And the indication to me is of objects that are reasonable size and are probably awash with water, bobbing up and down out of the surface,” he said.

How old are the images?

They were taken by commercial satellite imaging company DigitalGlobe on Sunday.

Why did we first hear about them on Thursday, then?

Basically, the Australians say, it’s because the Indian Ocean is a very big place. The maritime safety authority said it took four days for the images to reach it “due to the volume of imagery being searched and the detailed process of analysis that followed.”

Who is running the search?

The Australians are in charge of the search in their area of responsibility, which includes a large area of the southern Indian Ocean off Australia’s west coast. Malaysia remains in overall control of the search.

How did they know to look in this area?

Investigators analyzing satellite pings sent by the plane concluded it was traveling along one of two arcs away from the Malay Peninsula. U.S. officials have said they believe the plane most likely traveled south and crashed into the Indian Ocean.

Searchers narrowed the area of interest by calculating the most likely locations based on time in the air, fuel usage and other factors.

It’s already been 14 days. Are we running out of time to find this plane?

The locator beacons attached to flight data recorders are designed to ping for at least 30 days, but will probably keep going at full strength up to five days longer, said Anish Patel, president of Dukane Seacom Inc., the Florida company that believes it made Flight 370’s beacons.

“Our predictive models and lab tests show 33-35 days of output before we drop below the minimal values,” Patel told CNN. “Depending on the age of the battery, it could continue pinging for a few days longer.”

Pinging is one thing. Finding the pings is another.

Not only is the area being searched vast, it is deep – up to 13,000 feet in many places. Given that the pingers can be detected from no more than about two miles away, they could be hard to hear if they’re on the bottom of the deepest part of the ocean.

Layers of different water temperatures could also make it tough to pick up the sound of the beacons, experts say.

LIVE: Latest updates on the missing Malaysia Airlines jetliner

What can we tell from fresh lead?

If this is the debris of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370, what happens next?

Difficulties may hamper Flight 370 search

Opinion: Search for MH370 highlights need for trust, unity in Asia

CNN’s Mike M. Ahlers contributed to this report.